IS IT ENOUGH? PERHAPS IT IS.......

after J.R.AHLE (1625-73) and J.S.BACH (1685-1750)

(2016)

10'

© Julian Grant

It is enough!

Lord, when it pleases you

Grant me release.

May my Jesus come

Now good night, O world.

I am going to the house of heaven

I go confidently, with joy

My great sorrow remains down below

It is enough!

Es ist genug,

Herr, wenn es dir gefällt,

so spanne mich doch aus.

Mein Jesus kömmt!

Nun gute Nacht, o Welt!

Ich fahr ins Himmelshaus,

ich fahre sicher hin mit Frieden;

Mein feuchter Jammer bleibt darnieden.

Es ist genug!

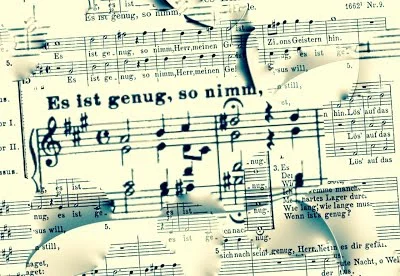

Es ist genug (It is enough) was written by Franz Joachim Burmeister (1633-72) and set to music by Johann Rudolf Ahle (1625-73), who was a predecessor of J.S. Bach’s at Mühlhausen. It was first published in 1662, as a vocal piece in six parts (2 sopranos, alto, 2 tenors, bass). The melody has caused comment, as the first four rising notes are all whole tones, which overshoots the customary major scale and outlines the tritone, or diabolus in musica. This, in earlier times, was a forbidden dissonance, and has since been used in Western music of all periods, to convey unease and disruption. Bach took the last verse of Es ist genug and harmonized Ahle’s melody for four voices as the final chorale of his cantata for the 24th Sunday after Trinity, O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort (O eternity, you word of thunder), BWV 60. This was one of the earliest of the more than 200 sacred cantatas that Bach composed during his Leipzig period: it was first performed on 7 November 1723. Compared to Ahle’s simple harmonies, Bach’s are unexpected, with, at one point, a sliding chromatic bass that very nearly implies the musical impressionism of Debussy, or even some floating jazz chords. The congregation would have known the chorale melodies and been expected to join in at the conclusion of the service, though whether they would have managed Bach’s harmonization is a matter for conjecture. There is a satisfying symmetry in Ahle’s melody, which balances the first four ascending whole tones with four final, almost identical descending pitches. This descending figure looms large in subsequent musical literature, becoming a symbol of farewell. The last three notes (like a horn-call, or ‘Three Blind Mice’) surface as the opening gesture in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no. 26 in Eb major op. 81a ‘Les adieux’ with the word ‘lebewohl’ (farewell) spelled out, each syllable attached to a note. Later, Mahler was to use and abuse these three notes to terrifying effect in the first movement of his Ninth symphony. Aficionados of twentieth century orchestral repertoire will know the whole chorale (in Bach’s version) as it appears in the final section of Berg’s Violin concerto of 1935. There is also a later set of variations on the chorale for viola and string orchestra (1986) by the Russian composer Edison Denisov (1929-96), and an orchestral piece by Magnus Lindberg (2002).

What struck me, after getting over being completely intimidated by all these illustrious predecessors, was the power of the cadences, the punctuation points that bring the music home, or not, at the end of each phrase. There is a colossal certainty about them, as if to bolster Lutheran faith and banish all doubt. I found them impressive and impassive, particularly from a 21st century vantage point, where musical language offer no such certainty. Hence I emphasize these cadences, and cast them as mighty pillars thatstand out in a sea of ambiguity. Is it enough? Perhaps it is…..was commissioned expressly to precede a performance of the Berg concerto, and uses exactly the same orchestra as the Berg. This meditation includes both Ahle and Bach’s versions of the chorale, albeit split up and in contrasting tonalities. Bach’s inner parts have a life of their own, and dominate the piece as it proceeds, blossoming into some long breathed, almost symphonic melodies. The ten minute piece concludes with a hard won affirmation of the final cadence and weaves the final notes of the chorale into an extended farewell.

© Julian Grant 2016

Commissioned by the Princeton Symphony Orchestra

First performed 9 October 2016 by Princeton Symphony Orchestra c. Rossen Milanov in Richardson Auditorium, Alexander Hall, Princeton NJ

For orchestra (2/1.ca/2.bcl/asax/2.cbsn/4221/timp/3 perc/harp/strings)